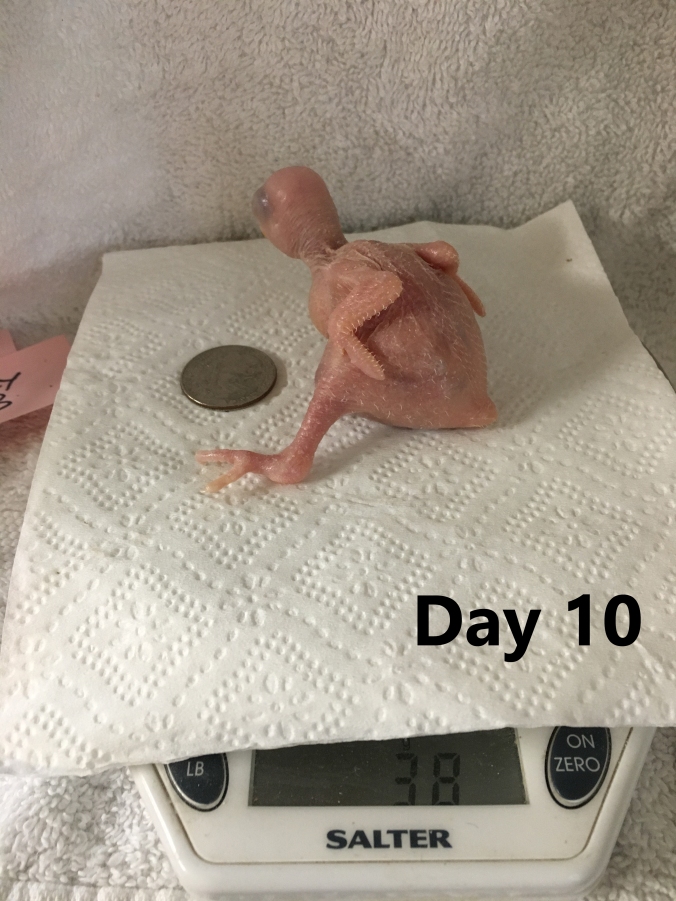

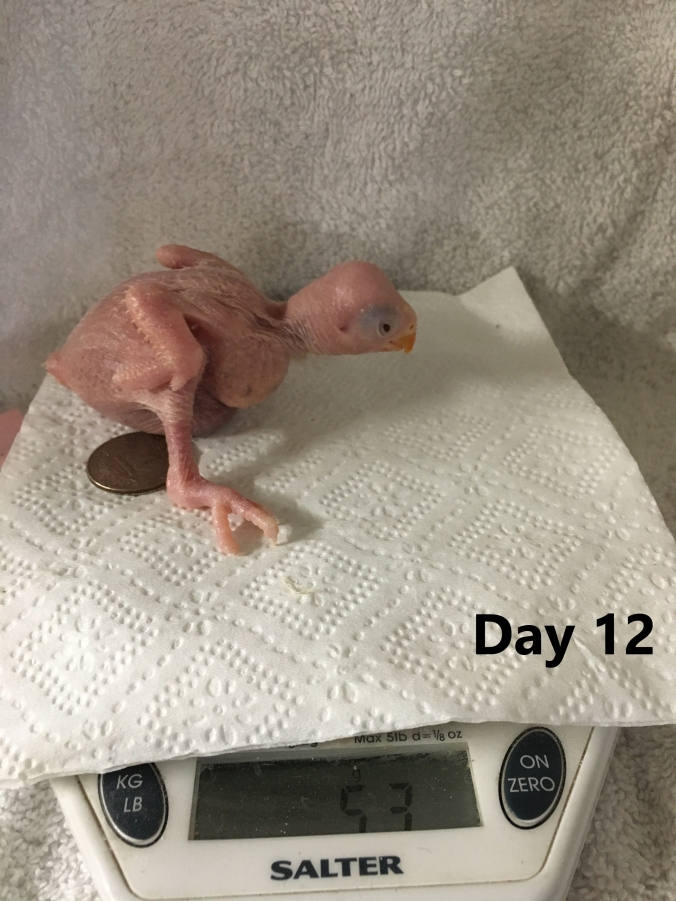

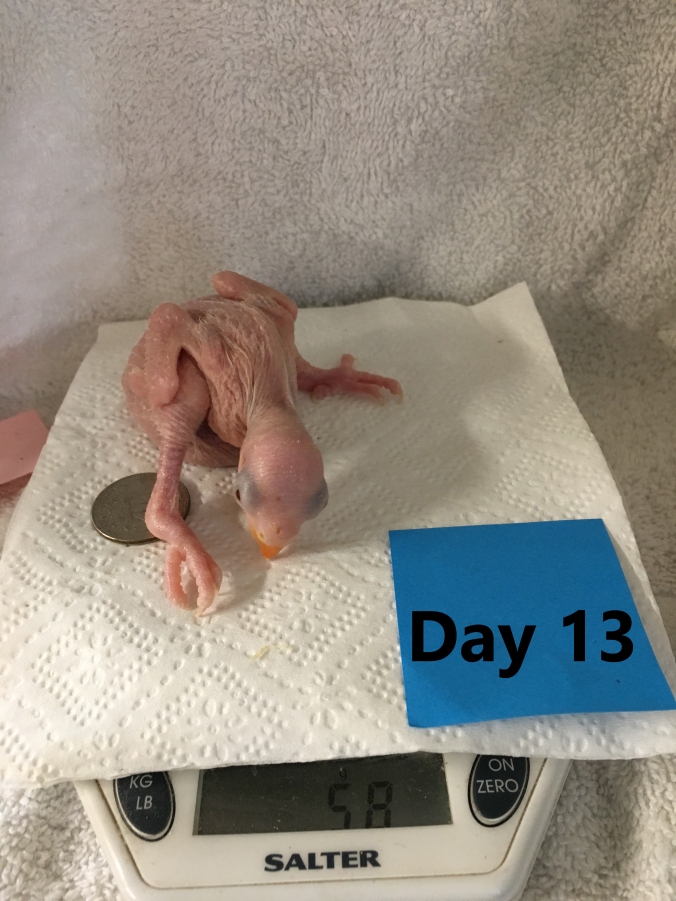

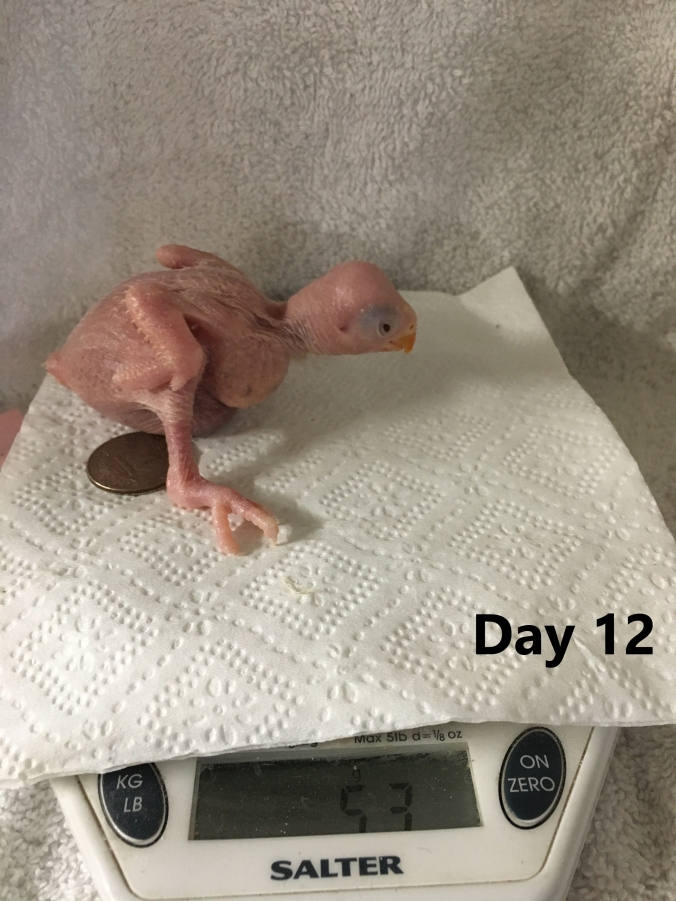

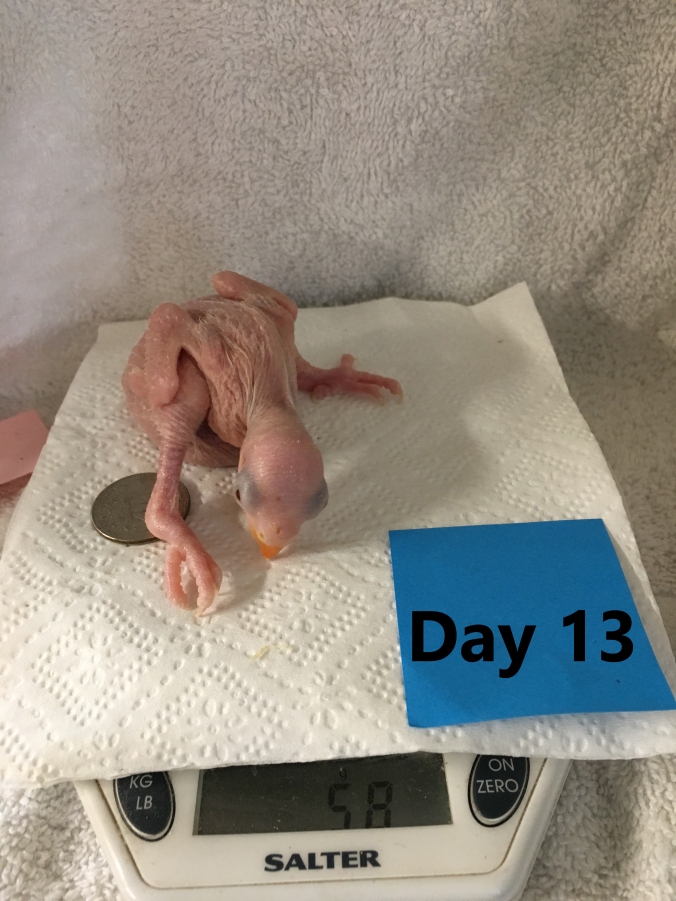

Keep in mind when viewing the weights that sometimes the crop is full and other times it is empty. This can cause the weight to vary.

© 2018 by Karen Trinkaus. May not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

Keep in mind when viewing the weights that sometimes the crop is full and other times it is empty. This can cause the weight to vary.

© 2018 by Karen Trinkaus. May not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

The purpose of this guide is to give beginning breeders and general idea of where their chicks should be at a certain age. It is important to notice stunting early so that it can be rectified before the chick falls too far behind.

All images are © 2004 by Karen Trinkaus unless otherwise noted and may not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

What kind of brooder do you use?

Unless you are raising chicks from the egg, you don’t need a fancy brooder. Very young chicks need strict temperature control. Older chicks in pinfeathers do not. My preferred brooder is a small fish tank or Kritter Keeper on top of a heating pad. This set up is cheap and very easy to transport. If you’re a hobby breeder this allows you to take chicks to your day job (if they allow such things).

I set the heating pad to Low. Medium can sometimes be alright if the bottom of the container it sufficiently padded. Always test with your hand to make sure the chicks won’t be burned. Chicks can be kept directly in the container or further divided into margarine tubs or baskets. If chicks are kept directly in the container then the pad should only be under 1/3 to 1/2 of it. This allows the chicks some movement from warm and cooler areas, though most don’t figure this out.

For bedding I use a paper towel and then a layer of shavings on top.

Which is best: syringe, spoon, or tube/gavage?

The syringe is my own tool of choice. It allows quick feeding and minimal mess. The spoon is much slower and messier. I don’t care for it because it may involve dipping back into the formula (contamination risk) and because it allows the formula to cool, but mainly because it’s tedious. Many people like the spoon because they think it gives them more of a chance to bond with their chicks. However, bonding can be achieved more freely outside the feeding time.

Tube or gavage feeding is frowned upon by many aviculurists. This is because it is often used by large breeding operations to quickly feed chicks in an assembly-line fashion. The problem is not with the method itself (though this instrument can be deadly in the hands of an amateur), but with the people who tend to use it. Often they won’t properly socialize their chicks at all. It also bypasses the chick’s normal feeding/swallowing and shoots food directly into the crop. I don’t recommend it for day-to-day feeding. Nevertheless, every breeder should own at least one tube. It is invaluable for feeding stubborn/ill chicks who may have no feeding response, and for administering medicine to an uncooperative chick.

How much do I feed?

You want to fill the crop but not stretch it out so much that it won’t drain properly. I suggest looking at parent-raised chicks for reference. My cockatiels are certainly more daring to swell chicks’ crops than I am. By the way, some chicks continue to beg even if they’re ready to burst so begging cannot be used as a reference. This is a good guide on crop health.

How often do I feed?

(based on the smaller species)

For the first few days chicks will take formula every 1 1/2 to 2 hours around the clock. Over the next week you can probably up this to every three hours, still around the clock. By the time the pinfeathers start coming in they should be up to every four hours, with only one night feeding (or none at all if you stay up really late and wake up really early). If I’m home I let the chicks decide- when they cry I feed them.

When do I pull the chicks for feeding?

Some breeders believe that in order to be tame chicks need to be hatched from Day 1 so that the first thing they see is people. This is utter nonsense. Tameness is directly related to how much time you spend with the chicks and what you do. Socialization during and directly after weaning is key. Leaving the chicks with their parents for a while is generally much healthier for the babies. I pull my chicks when they have pinfeathers, but well before the feathers start opening. For something like cockatiels this would be about two weeks. For larger species it will be later. Go by developmental stage.

What temperature do you feed the formula?

I go by Parrots: Handfeeding and Nursery Management with all my measurements. I begin sucking formula into syringes at 110 degrees. It cools quickly. Birds will often refuse formula if it is too cold. Too hot and it will burn them. You can keep formula warm by floating your formula cup within a larger dish of hot water.

What disinfectant do you use?

There are many on the market- each killing it’s own type of pathogens. I use bleach. It’s like duct tape- works for everything. Add one teaspoon of bleach per gallon of water. The only problem with bleach is that it tends to corrode your stuff over time.

What formula do you use? Do you add anything to it?

I use Kaytee Exact formula. Commercial formulas are designed to have all the nutrition a bird needs and you’re not supposed to add anything to them (it will upset the balance). Still, I add Spirulina because I hear it’s good for the immune system and sometimes peanut butter during weaning (the babies eat less so I want to make what they do eat more fatty).

Most food will be played with at first. Remove uneaten soft foods after an hour so they don’t spoil.

How do I wean babies?

Weaning is probably the most stressful part of a bird’s life and the most agonizing for the feeder. Weaning starts when your babies start refusing food. They’ll beg to be fed just as usual and then as soon as you point the syringe at their mouth they’ll clamp their beak shut. Even before the bird begins refusing formula you should be adding solid foods to the cage. Try softer things, or things that are easy to pick up. I start with bananas, Cheerios and parsley. Check the chick’s crop a couple times a day (just move those feathers aside) to see if it’s eaten anything. Once they actually start eating the food I offer a wider selection, starting with softer foods and then working up to harder. Expose them to as many different textures and foods as possible.

The chicks should naturally cut back on formula on their own, though many will beg for formula as a comfort thing. In the wild parents may continue to feed their chicks well past the point when they can fend for themselves. I’ve heard that macaws have been witnessed feeding their offspring for up to two years. My own Goffin cockatoo enjoyed comfort feeding until she was a year old. I can’t say when to stop formula completely- whenever the bird is eating completely fine on it’s own. You may still want to offer formula on occasion just in case.

Weaning is not something to be pushed. Birds will wean at their own pace. Forcing them to wean faster than this will result in poorly-socialized chicks with attachment issues.

Additional Tips:

Links:

Slow, Sour and Yeasty Crop Remedies– Great read that goes into more detail about handfeeding.

Handfeeding Birds from Conure to Macaw

Handfeeding Cockatiel Babies (video)

Want to submit a recipe? Email me!

All- Purpose Bread

This was originally a recipe for an apricot nut loaf. Bread is one of the best things you can make for your birds. Why?

The ingredient list here is only a basic guideline. Like I said before, you can add just about anything you want. Fruits and nuts bake great, veggies usually don’t. Warning: don’t add tomatoes unless you REALLY love the smell. The bread will reek of them while it’s baking and whenever it’s re-heated.

Ingredients

3/4 cup dried fruit

1/2 cup boiling water

1/2 cup Crazy Corn

1/4 cup peanut butter

1 tsp Spirulina

2 tbl melted butter

3 eggs with shell

2 cups flour

2 tsp baking powder

1 tsp baking soda

1/2 cup chopped walnuts & pine nuts

Instructions

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. In one bowl mix all the powders (flour, Spirulina, baking soda and powder). Throw everything else into another bowl. Make sure everything is well mixed and eggs shells are well crunched as the bread will be very thick. Add all the powders to your “everything else” bowl. Mix well again. Batter should be very thick and chunky. If it’s not add more fruit/nuts/whatever. Pour in pan, bake 55-60 minutes. Let bread cool before cutting. Cut bread into slices (however much you will use at once) and store in a ziplock baggy in the freezer. Defrost however much you need later.

————

Simple Eggfood

All birds, especially breeding pairs, need protein. This can be supplied in many ways. Most poultry owners and some parrot owners buy their birds lay mash. Others prepare bean mixes. Another easy way to give your birds protein is to serve them eggs (and no this is not cannibalism). Not only does it provide protein, but if you mix in the eggshells they’ll get extra calcium as well. As one of my AVS professors put it, “The egg is the most complete form of nutrition.”

Ingredients

The number of eggs depends on how many birds you’re planning to feed. One egg goes a long way. If you’re like me and you’ve raised quail at one point or another, 4-6 quail eggs equals one chicken egg. There are also many extras you can add if you like to make a little omelet: peppers, veggies, and beans.

Instructions

Take out a bowl or measuring cup that is microwave-safe. Toss entire egg into bowl and crunch up well. Put bowl into microwave and heat until the egg is puffy and there is no “goo” left. This may take 90 or more seconds depending on the strength of your microwave and how many eggs you’re cooking. Alternately, cook on the stovetop. Place egg on plate and crunch further, making sure the shell is well mixed and not clumped together. Serve while warm and take out unfinished portion within an hour as it will start to spoil and attract ants.

————

Rice Pudding Muffins (submitted)

Ingredients

2 cup apple juice

2 cup instant rice

1/4 cup raisins or dates

1 15 oz. can of sweet potatoes (use 1/2 the juice from the can also)

3 tbsp honey

2 tsp cinnamon

1 tsp nutmeg

1/4 cup flaked coconut

3 large eggs

1 box of yellow cake mix

1/4 cup chopped nuts

Instructions

Add the raisins to the apple juice and bring to a boil in the microwave. You’ll need a large bowl. After the juice boils for one minute remove and add instant rice, cover and allow to cool. Set this aside. Blend sweet potatoes with honey, cinnamon, nutmeg, coconut and eggs until smooth. In a large bowl empty the box of yellow cake mix and then fold in the rice mixture and add the potatoe mix. Stir everything together and bake a 400 degrees in muffin tins until golden brown. Makes about 3 1/2 dozen muffins.

“who can shed light on what happens to a cockatiel loose in minnesota”

– post on Toolady.com

Few things have ever made me feel quite so helpless as watching an escaped budgie fly off and vanish from sight. Hopefully nothing like this has happened to you and you’re reading this as a precautionary measure only. However, it’s much more likely that your bird is currently lost. Perhaps you’ve found a bird and are wondering what to do next. Whatever your reason for reading this article, I hope it helps enlighten you on how best to deal with this heartbreaking experience.

There is one very simple way to prevent birds from escaping. Unfortunately, most people are lax about it and consequently I receive numerous questions about lost and found birds. Smaller, lightweight species can fly well with only one or two primary feathers. Add a gust of wind and you may never see your bird again. Clipping the wings regularly is very important if you want to prevent escapes. However, one clip per molt just doesn’t cut it (no pun intended). Birds do not shed all their feathers at once- they grow new ones a few at a time. This means that it takes a while for the primaries to grow back. It only takes one feather to lose your bird. Waiting until all of them have grown in before clipping can be disastrous, but few people are willing to bring their birds in to be groomed for each individual feather.

I highly recommend learning to clip your own birds. Grooming can then be done at home, per feather. If you have a good relationship with your bird this should not be a problem. Clipping is a painless procedure that takes mere seconds when done correctly. Your bird may be slightly stressed the first few times, but will not hate you for it. After a while clipping becomes routine- your bird won’t like it but will at least know what to expect. Even Fry, the conure that hated hands, did fine during clipping. He would try to run if he saw hands coming and wriggle away once I had him, but he trusted me not to hurt him and would never attempt to bite. If you have a large or squirmy bird like Fry, you can hold it while someone else does the clipping. Birds that are very tame and used to handling may not need to be restrained at all- yet another area where proper socialization helps.

Another way to prevent escapes is to limit outdoor time. Let the bird sit by the window for part of the day or build a sunroom both you and your birds can enjoy. If you must take your bird outdoors, don’t take any chances. Even if your bird can’t fly there are still dangers. What if a hawk or cat gets it? What if the bird is startled and manages to get into a tree, climbing up out of your reach? Or worse yet, manages to get into a neighbor’s yard? What if someone steals it? Murphy’s Law always applies to birds, so plan accordingly. Take you bird outside in a cage or on a harness. If brought out in a cage make sure you secure sliding doors. If you have a young bird, start training it to wear a harness while it is still open to the idea. Older birds are going to be much slower to adapt.

Here’s another tip that won’t prevent escapes, but will make your life easier if your bird does get loose: teach it to sing/whistle a tune. This works best with birds like male cockatiels, who love to whistle along. A unique tune will help you keep track of your bird should it get out of sight. Where did it go? Which tree is it in? If your bird sings you can better pinpoint its location.

I’m often asked about survival odds. Some people hear about wild flocks of parrots in California and Florida and think that their birds have a pretty good chance. Unfortunately, they don’t.

True, budgies and cockatiels are very hardy. However, all our pet birds are currently bred in captivity. Australia has had laws against exporting wildlife for some time now, meaning that Aussie species are even farther removed from their wild ancestors. Captive bred birds are not very well equipped to survive in the wild. They are not used to the weather. They are not used to avoiding predators. They are not familiar with the native sources of food or where to locate them. Many cannot even fly very well so even if they wish to return they can’t (again proper socialization is important, as is proper clipping!).

The wild flocks of introduced parrots that you hear about were established back when parrots were still imported in large numbers. They were most likely wild birds, caught and imported, which then escaped or were released. Most of these parrots are also larger South American species like amazons and conures. Larger parrots would have fewer predators and be able to access better food sources. It’s not hard to see how larger, wild caught species, introduced as groups into fairly mild environments (Florida and California) could learn to adapt and survive. However, it is unrealistic to expect a single smaller bird, captive bred but native to the Australian outback, to survive a Minnesota winter. Your bird’s best chance at survival is to be found.

There are two scenarios when a bird escapes:

Scenario #1 is bad; #2 is virtually hopeless. YOU HAVE A MUCH BETTER CHANCE OF GETTING YOUR BIRD IF YOU KEEP IT IN SIGHT. Unfortunately, many birds take off flying in one direction and continue to do so until they run out of energy. Parrots are not homing pigeons and will not find their way back on their own.

Scenario #1- KEEP THE BIRD IN YOUR VIEW. If you can’t see it, keep track of it by sound. Having someone nearby really helps here, as you risk your bird flying out of sight should you choose to go indoors and get something to help you catch it. Aside from keeping track of where it is, it is also important not to startle it into flying again. If your bird doesn’t trust you much, this will be difficult. If within reach, I find that using a long perch helps. Get the bird to step up and then slowly move it to a better location. Attempting to grab an untame bird will only result in it flying further away.

Getting a bird down from a tree is tough. Even tame, loving birds will be reluctant to see what the fuss is and climb down on their own. Amazons are notorious for climbing higher into a tree, or flying to another one as soon as you are about to catch them. In a case like this a hose helps- spray ABOVE the bird so that it rains DOWN onto them. Really soak them. It will make it more difficult for them to fly. Then have someone climb the tree (if possible, ask around the neighborhood) and get the soggy psittacine. Lures can also be used to get a bird down. Leave out a cage with food in it and the door open. Bring out another bird (preferably a friend of the loose one) in a cage and place it next to the first cage. Play a tape of recorded bird noises.

Scenario #2- This is BAD. Your only hope here is to a) locate your bird or b) hope someone else does. First search the neighborhood. Call out to your bird and pray you can find it through sound. If that fails, put up signs around the neighborhood and post on social media lost/found groups. Also contact every local person who owns birds (especially if they keep them outdoors) and let them know to keep their eyes peeled. Birds are attracted to other birds, and yours may very well be attracted by the sound of theirs. I’ve inadvertently adopted several stray budgies this way.

People are often devastated when they lose their pets, and it is unfair to assume ownership of a lost bird without at least attempting to find the owner. Check the local pet stores, vets, social media, and newspapers for ads about lost birds. If you can’t find the owner you can keep the bird yourself, providing you can properly take care of it, or give it to someone who can.

I keep all my breeders outdoors and they do attract escaped birds. My cat is the first one to notice. He never gives my aviary birds a second glance since he knows he can’t get to them. If I see him staring at something by the aviary I know there’s a loose bird.

I’ve had three escaped budgies hanging around my aviary this year, two of which I managed to catch. The first was easy- I just walked over and grabbed him. The poor thing was starving, emaciated and trying desperately to find a way into the budgie cages. I placed him in quarantine and a day later notice that he seemed to have bulked up, an impossibility. I examined him and found that his skin was stretched taut, especially around the thighs. He had a punctured air sac and the area under his skin was filling with air. I called my vet and made an appointment, then made several pin pricks to his swollen thighs to release the air. Luckily this solved the problem. After a vet visit and 30 day quarantine, he was ready to join my flock.

The second budgie I caught was just last month (December 13th or so). She was much better off, hanging out in the neighbor’s yard up in a tree all day. It was cold out and she didn’t seem to be enjoying herself. After about a week I found her eating seed spilled from my aviaries. There’s about a one foot gap between my second aviary and the roof and I managed to scare her from on top of the cages into this space. Once in the gap she was reluctant to leave, though she’d run/fly all over the place trying to avoid my net. It took about 20 minutes and a second person, but we managed to net her. She too went through quarantine and joined my flock.

© 1997-2016 by Karen Trinkaus. May not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

Proper wing clipping is essential for pet birds. Too many flighted birds escape, crash into windows, are killed by fellow pets, fly into ceiling fans and open water containers, etc. Some people claim to have “bird-proofed” their home enough to allow free-flight, but there could still be many unforeseen hazards. If you do not live alone, you also have to rely on other people to close doors and windows and keep them closed when a flighted bird is out. One small miscommunication could lead to an escaped bird. In addition, free-flight causes some birds to become territorial and hard to handle.

When to clip:

Birds do not molt all their feathers at once. If they did, they wouldn’t be able to forage for food and escape from predators. Instead, they lose one or two feathers at a time in alteration. Since most birds (especially the smaller ones) can fly with only one or two primary feathers, it is important that you clip each individual feather after it’s grown back. Don’t wait until all the primaries have grown back before taking your bird to be clipped.

Many people seem afraid/unwilling to clip their own birds. It’s a simple procedure that anyone can (and should) learn. Some people are afraid their birds won’t like them if they do the clipping themselves. This is nonsense. I’ve been clipping all my own birds for over 25 years and no one has ever held a grudge. As long as clipping is done quickly and painlessly (don’t cut bloodfeathers) birds will forget about it five minutes later.

How to clip:

I highly recommend getting your birds used to playing with their wings. It makes clipping much easier. If your bird does not allow you to touch or extend its wings, you will need to restrain it. Use a thin shirt for small species and a towel for large ones. Small birds can be held in one hand and clipped with the other. With larger birds an assistant is needed. One person should hold and the other should cut, although an experienced person can do both.

Catch the bird using a towel and position it so that the head is out. You want the cheeks/jaw between your fingers. Do NOT squeeze your bird tight. Grasping the chest is dangerous and unnecessary. The goal is to restrict movement of the wings and the beak. A flailing bird can injure itself and a stray beak will happily take a chunk out of you. The lower mandible needs be between your fingers. If positioned correctly, this prevents the bird from biting. The wings should be held against the body until they are brought out for clipping.

Small birds easily fit in one hand. I usually catch with my right hand, then move them to the left while I clip (I’m right-handed).

The feathers that need to be clipped are the primaries (1). These are what provides the power for flight. In small birds 7-10 feathers should be cut because these guys can get lift very easily. Large species often fall like rocks when only a few are cut. Two – five is standard for larger species. Never cut too far up (see red line). There should still be some space (at least a cm) between the edge of the cut primaries and the feathers above.

Feathers are made of keratin- the same stuff fingernails are made of- and do not hurt when cut. The only exception would be bloodfeathers. Never cut a bloodfeather!

Feathers are easier to clip than nails because it’s easy to recognize a blood feather and much harder to find the vein in a nail. Some people buy cement or sandpaper perches in an attempt to keep nails trimmed. These can actually irritate bird feet. As with all perches, it is important to have a variety of textures and widths so that feet don’t develop sores. A single grooming perch is fine so long as your bird has other options like wood or rope.

When to cut:

Learn to judge on your own. If your bird is tripping or the nails are catching on your clothing then it’s time.

How to cut:

Some birds don’t even need to be restrained for nail clipping. With both my GC conure and my tiel, I can let them sit on my finger while I just reach over and snip. You have to be careful with this though since they can move. For my Goffin I just hold her foot while she’s perched and clip. Routinely playing with your bird’s feet can go a long way toward making nail trimming easier.

I use human fingernail clippers or nosehair clippers (for smaller species). Get out a towel (or old thin t-shirt for smaller birds) and some flour (in case of bleeding). Some people use Kwik-stop but I’m not a fan.

With small birds that don’t bite very hard you can usually do the job yourself. With major bitters or larger birds it’s better if you have two people. One person should towel the bird and keep the beak out of the way while the other person holds the feet and clips. This should all be done as quickly as possible to minimize stress.

You want to snip off the tip of the nail. If you clip too far up you’ll hit the vein and your bird will bleed. In black nails the vein can be virtually impossible to detect, though if you’re experienced you can avoid it by just using your intuition. Beginners can try pressing down slightly with the clippers first- if the bird flinches, chances are that’s the vein. Some birds squeal or flinch at any pressure though, with or without a vein. Not all cut veins bleed right away so keep an eye on the bird for a minute or two after cutting. Most veins start dripping once the bird begins walking around. Flour stops bleeding pretty well but you may have to hold the bird still for a few minutes to keep the flour from being rubbed off.

Healthy beaks do not need to be groomed. Unfortunately, there has been a bit of hype about grooming beaks lately, mostly to try and sell beak sanding tools. Only birds with grossly deformed beaks need any grooming. Scaly mites, injuries and vitamin deficiencies can cause the beak to overgrow. In a case like this the bird should be taken to a vet to have the beak done professionally. The beak is not like a toenail. Though it may look solid and plain, the beak is in fact a highly sensitive structure and should only be trimmed by an experienced professional (i.e. avian veterinarian, NOT a random pet store employee).

The left conure needs a beak trim, the right does not. If you look closely, the left bird’s beak is not rounded as it should be, but rather angles down in a straighter line. It’s a mild deformity but has led the beak to overgrow (it took 12 years to get overgrown).

This sun conure has scissor beak, another deformity in which the two sides veer off and do not meet in the middle. Because the upper and lower bill do not grind together during normal use, a bird with scissor beak will need routine beak grooming. As you can see here, the lower bill has overgrown.

© 1997-2016 by Karen Trinkaus. May not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

Feathers are made up of the same material as fingernails. They help birds regulate their temperature, allow them to fly, facilitate communication, and can indicate the overall health of a bird.

Maintenance/Preening

Aside from wing clipping, feathers require no extra maintenance on your part. Like cats, birds keep their own feathers clean. They will spend hours a day preening their feathers to keep them in good shape. Preening involves gathering oil from the uropygial gland, located at the base of the tail, and spreading it over the feathers. Each feather is individually run through the beak and straightened.

A few species- cockatoos, cockatiels, and African greys- have specialized down feathers that dissolve into a fine keratin powder. This powder performs the same function as the oil from the uropygial gland. However, it makes these species extremely “dusty.” If you keep these birds indoors you may need a good air filter. If a powder species doesn’t seem to be producing any powder, take it as a sign of illness. PBFD is one possible cause.

You can help your bird keep itself clean by allowing it access to a shallow dish for daily bathing, or by spray misting it. I do not recommend applying any kind of product to a bird’s feathers. There is no need. Birds produce their own oil/powder naturally and do not need any special “conditioner.”

Molting

Pinfeathers dot this budgie’s head. (X)

Twice a year your bird will molt. Molting is the process of losing feathers and replacing them with new ones, not unlike a dog shedding. It is done gradually, so while you may find lots of excess feathers in your bird’s cage, your bird will not appear to have lost anything. New feathers grow in encapsulated by a waxy sheath. You will see these pinfeathers start to dot the top of your bird’s head where it cannot reach. Pinfeathers can be itchy and if your bird allows head scratches you can help release the new feathers by gently rubbing them between your fingers. Normally this is done by flock mates.

Blood feathers are pinfeathers which are still being fed by a blood supply. Flight feathers grow in as blood feathers and can bleed profusely if broken open while they are still growing in. If a bird has a broken blood feather you can attempt to stop the bleeding by putting flour on it. If that doesn’t work, grasp the feather at the base of the skin with needle nose pliers and swiftly yank it out in the direction it is growing. Only yank as a last resort as you can cause damage to the follicle.

Stress Bars

If you’re finding lines across your bird’s feathers then you have a problem. Stress and malnutrition during a molt can both cause new feathers to emerge with stress bars.

Plucking & Feather Loss

The first thing to do is determine why a bird is losing feathers. Not all feather loss is caused by plucking, and not all plucking is the result of neglect. Giardia can cause intense itching, which can then lead to plucking. Thankfully, it can be treated. PBFD causes severe feather loss and compromises the immune system. There is no cure for PBFD. If your bird is losing feathers it is best to take it to a qualified avian veterinarian first to rule out any medical causes. Make sure your bird is receiving a good diet and that the humidity isn’t too high or low. Many of our pets come from tropical climates, so if you live in an exceptionally dry area this could be exacerbating any problems.

It’s usually quite easy to tell if a bird is plucking itself. Birds can only pluck the areas they can reach, so a bird that is plucking itself will be losing feathers on the chest and back but never the head.

This African grey exhibits overall poor health in addition to plucking of the chest and back. All the remaining wing and tail feathers are bent, drab, and stressed. Photo by Tambako the Jaguar.

This blue and gold macaw had plucked its entire chest and legs. Photo by Rodrigo Soldon.

Feather plucking is a difficult habit to break once it’s begun, so swift intervention is always best. A bird could be picking for any number of reasons: poor health, parasites, stress, or boredom. Birds without anything to do rapidly turn to destructive behaviors like plucking and even self-mutilation. Make sure your bird has plenty of toys/activities AND companionship.

If you adopt a feather plucker, a proper home will go a long way towards halting the plucking, but it can still remain a habit. If this is the case, make sure your bird has plenty else to do. Foraging toys, chew toys, exercise, etc. will all help. You can also get a special vest to help protect the chest.

Some birds are plucked by their mates. This is actually quite common and not a cause for concern, so long as it does not progress to something worse. When a mate is doing the plucking, feather loss is usually restricted to the head because this is where they mutually preen.

Vita has been plucked by her mate for years. Notice how it is completely confined to the head.

Injury is another source of feather loss. If a bird is severely injured then the feather follicles may be damaged beyond repair, preventing any new feathers from growing.

Blue boy had a head injury years ago, and retains a quarter-sized bald patch to this day.

Copyright © 2001 by Karen Trinkaus unless otherwise noted and may not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.

There seems to be a lot of misinformation online about bands. Pet owners are attempting to use band information to find out more about their birds, which is a good thing. However, the reality is a lot more complicated. First I’m going to discuss the basics of bands and then I’ll address some of the common misconceptions.

What are bands?

Bands are like little ID bracelets. They can be metal or plastic and are located just below your bird’s ankle. There are several types of bands.

Plastic bands on canaries. Photo by steve pj2009.

Plastic Bands

Plastic bands are most commonly used to identify softbills. They allow aviculturists to quickly distinguish between different birds at a glance- particularly important if you don’t want to catch your birds every time you need to tell who is who. Sometimes birds will be banded several times on multiple legs. Breeders may put one band on each leg and then clip off a specific band when they discover the sex of a bird.

Open band removed from my mitred conure postmortem.

Quarantine Bands

Until 1992, the United States imported large quantities of wild caught birds. These birds were held at quarantine stations before being offered for public sale. All birds that went through quarantine were banded with open bands. If your bird does have a quarantine band you can look up where it was imported. All quarantine bands were open bands, as they were applied to adult birds.

Open Bands

Open bands are metal and usually round (not flat). The only benefit of open bands is that they can be applied to adult birds.

African grey chick wearing closed band. Photo by Papooga.

Closed Bands

Domestic-bred birds wear closed bands. These bands are flat and can be made of metal or plastic. They can only be applied during a brief window of time when the chicks are young. If banded too early, the bands will fall off. Too late and you won’t be able to fit them on the feet.

What information do bands carry?

Bands can tell you many things. The information given varies, but often the state, year, ID number and breeder are given. For instance, my cockatiel Melonie’s band says “CA LS 92 52.” This means she was bred in California (the state is often written sideways), her breeder’s initials or business abbreviation is L.S., she was hatched in 1992 and her ID # is 52. Breeders can pick and choose what they want on the bands. Some will not contain a year since the breeder may not use up all of his or her bands in one year.

Why is banding important?

Bands provide positive ID of a bird. If a bird is purchased and then later returned, the seller can verify that the returned bird is in fact the same one sold. They can be used as identification in case of theft (unless removed- microchipping is better). Closed bands are also fairly good proof that a bird was captive breed.

Are bands harmful?

Open bands can be dangerous because the small slit in them may catch on things, like the cage wire, especially if not closed enough. Most of the time bands are very safe. Hens usually do not attack babies with bands nor do birds mind them at all. Injuries can occur when a band catches on something, but most of the time this is the result of an unsafe cage. If your bird is banded be extra careful that no toys could catch your bird’s band.

Feisty Feathers Bands

I try to band all the chicks I can. My cockatiels are banded with my National Cockatiel Society number (45F). Indian ringnecks and green cheeks are banded with my aviary name (FSTY).

Can I look up where my bird came from? Its age? Breeder?

Yes and no. Aside from specific clubs, which have their own bands and registries, there is no comprehensive banding system or database. Aviculturists who breed show animals like English budgies are far more likely to participate in such a system than someone who sells to the pet trade. Many breeders are going to want their own system in place, and may not use a club since their bands are often not very customizable.

open band

Don’t assume the year is accurate.

The first year I started banding my own birds I got the year printed on my bands. Big mistake. Bands came in lots of 25 and I didn’t come close to using half of my bands that year. So I could either throw them away the following year or keep using them with the incorrect year. This is why most breeders don’t even bother with a year.

Don’t assume the state is accurate. Or the breeder. Or anything, really.

I recently acquired a pair of African greys from someone who was moving to China. This breeder was trying to unload all their stuff in prep for their move, and since I’d bought their last available pair they came with a lot of extra stuff: net, handfeeding formula, perches, and unused bands. Even though this was a California breeder, the state stamped on the bands was PA.

This brings me to another point- breeders can totally swap bands. I think the first time I bred ringnecks I ended up borrowing bands from a friend because I only needed a couple. When my grandfather died I got all of his old bands. I didn’t use them, but I certainly could have.

My point is that nothing about bands is certain. Pet owners have a tendency to give bands the same sort of authority as dog licenses or microchipping, when it’s really more like your neighbor borrowing a label maker so they can organize their closet. All you can know for certain is that closed bands were applied to babies before leaving the nest.

Banding is a way for breeders to distinguish between individual birds, not for people to be able to track down a breeder, know the age of their bird, etc. Some breeders make their banding system public, but most don’t because it’s an internal ID system. Many breeders don’t really care if their bands are “accurate” because again- it’s just to be able to tell the difference between similar birds. A few will have nice records and a formal system but many will not. It really depends on the breeder. So while you can use the information on a band to make a guess, there is no guarantee your guess is going to be accurate.

Here are some links if you do want to look up more information on bands:

This information pertains to the red-fronted kakariki (C. novazelandiae) but most of it can also be used for yellow-fronts (C. auriceps).

This information pertains to the red-fronted kakariki (C. novazelandiae) but most of it can also be used for yellow-fronts (C. auriceps).

In the Wild

More detailed ecology here.

Kakarikis are native to New Zealand. There are several species, most of which are endangered or extinct. New Zealand is a small group of islands southeast of Australia. Like most islands, it has very unique wildlife. Until man came, there were no mammals and birds evolved to fill in niches normally taken by mammals. Many of them became flightless and have no fear of predators. When man brought mammals like cats, weasels, and rats, most of the native birds were wiped out. Luckily the kakariki can fly. Still, they spend as much time on the ground as they do in the trees.

Kakarikis have long feet and toes which they use to scratch about on the ground like chickens. Their feathers are also elongated and fluffy to help protect them from the cold (New Zealand is right above Antarctica).

Kakariki feathers are elongated and fluffy.

Contrast with desert species A (cockatiel) and tropical species B (green-cheek conure).

Compare kakariki feathers with those from other species: the cockatiel (A) from the deserts of Australia and the green-cheek conure (B) from tropical Brazil. The down is concentrated near the skin and the tips are dense when compared with those of other species. Elongated feathers can be erected to trap heat near the body. Unfortunately these adaptations can work against them in captivity. Kaks can overheat easily.

Noise

Kaks have a very pleasant “wa wa wa” sound and males can be talented talkers.

Lifespan

15-20

Sexing

Kaks are dimorphic so there’s no need for DNA or surgical sexing as long as you know what to look for. Males are about 15 grams heavier than females, and have bigger heads and wider beaks. The females look very thin and dainty. Most males also seem to have a brighter shade of red than hens. Chicks can be sexed by the width of their beaks when their pinfeathers are just beginning to open. Use the following pictures as a guide to sexing your kaks.

male (left), female (right)

female (left), male (right)

Weaknesses

Kaks may be susceptible to aspergillosis. I’ve never had a single case of aspergillosis in any of my other species, yet it killed several of my adult kakarikis over the years. That said, I have yet to confirm this problem with other kak breeders and the problem stopped when I moved to Northern California. It could be that my first location just had a lot of spores locally and the kaks were more likely to pick them up and/or develop infections.

Baldness is common in kaks, particularly hens. Not all birds seem to have this problem. The feathers usually grow in during a molt and the bird will look perfect for a week or so, but then the feathers will drop out again. The cause may be genetic (kaks aren’t very common in the U.S. and many have been inbred) or overzealous preening on the part of the male. Kaks seem to drop feathers quite easily, so I can see how a little rough preening would knock quite a few out. My hens look really ratty in the breeding season.

Many of you have reported seizures or strange trances in your pet kaks, and have asked me if this is normal. This year was the first time I’d ever experienced it in my own flock. I placed my male yellow-fronted kak in a brown paper bag so that I could weigh him. When I took him out, he lay on the ground and appeared to be dying. I immediately rushed him to the vet, certain that he would be dead when we arrived. Instead he slowly started acting normal again- first he stood up and wobbled around, and soon he was hopping about the cage. By the time my vet saw him, he was acting normally.

My vet (an excellent avian vet, by the way) told me that some species go into weird trances or even have seizures when certain procedures are done. She said that it really freaks out the owners, but it is perfectly normal. I can’t remember all the species she mentioned, but she said Meyers parrots would go into seizures when their nails were trimmed. Odd and frightening, but they always snapped out of it eventually. Like I said, I’ve gotten numerous letters about seizures, trances and stumbling in kaks, so it appears that they may be one of the species that reacts like this.

Yellow-fronted male

Husbandry

Kaks are very busy birds who want to be everywhere at once. They’re the only psittacine that makes me feel bad about clipping wings. Breeders should definitely be kept in an flight and pets should be let out as often as possible. Since kaks are so curious you should make triple-sure that there are no hazards in or around the cage. And be wary of escapes! I’ve seen my kaks perform somersaults in the air to avoid a net. Feed cups should be covered. These guys will flick food everywhere with their scratching behavior. Also, kaks do enjoy running around upside down on the ceiling so I’d advise at least part of the cage ceiling be wire.

Just try to catch us, Mom!

Breeding

The first thing you need to make certain of is that your birds are not hybrids. Red-fronts only have red and it’s found on the crown, back past the eye, as a sort of stripe leading to eye and as a spot behind the eye. Yellow-crowns do not have the stripe or the spot near the eye, but have a small patch of red just above the cere and a yellow patch extending past over the eye. Hybrids look like yellow-crowns with a more orange color and sometimes a partial spot or stripe.

Kaks can be bred similarly to cockatiels and Aussie parakeets. I’d advise only keeping one pair per aviary due to their curious nature. If offered multiple nestboxes they will start a clutch in one box and when the first clutch gets older the hen may start a new clutch in the second box while the male finishes raising the first. They are very prolific for their size (females about 55 grams and males about 75), laying 8-12 eggs. Often the hen cannot properly incubate such a large clutch and some may have to be taken out. Babies quickly begin to look like parents so banding is a good idea (banding is a good idea anyway). For a week or so after fledging their beaks will be beige but then will turn the typical silver tipped with black.

They will kick everything out of their feed dispenser/dish. Every inch of their cage will be utilized. There is no dead space with kakarikis.

Diet

Regular psittacine diet. While most of my birds go right for the corn in their frozen veggies mix, my kaks eat the peas first. One of the most wonderful traits about kaks is that they are so curious. Not only does this make taming easy, but conversion to pellets as well. With most kaks, this is as simple as adding a bowl of pellets next to the seed dish for a day and then removing the seed the day after (just make sure they’re eating it if you switch cold turkey like this).

Personality/Behavior

Kaks were what inspired me to name my business Feisty Feathers. They’re a lot like big budgies- very animated, playful and chatty, but not very cuddle. I’ve handfed both budgies and kaks. It’s a joke. They want to be fed but they’re too hyper to sit still and feed. They want to over there or doing at that. It’s a miracle to get their crops completely full. Kaks make very entertaining pets if you can handle a bird that will get into everything.

Articles and images copyright © 1997-2011 by Karen Trinkaus unless otherwise noted and may not be reprinted or used in any way without the author’s permission.